The artist perched on the crest of a dune, sketchpad in hand. He worked swiftly in pastel, racing to capture the scene before he lost his vision in twilight shadow.

The dunes undulated, a serpent wriggling its way round the coastline. A mild breeze blew in from the ocean, rustling the green scrub and rattling the yellow, white and blue wildflowers that burst in bright patches over the dun, sandy heights. A few gulls soared overhead. Their cries, the repetitious washing of surf on the shore, and the wind soughing through the sparse foliage were the only sounds heard in this remote place.

The artist stopped sketching. He set down his pad, pulled off his wire-rimmed glasses and rubbed his tired eyes. A ray cast by the dying sun slanted across his white-stubbled jaw, highlighting his hard, thin face like a moonbeam limning a carving on a headstone.

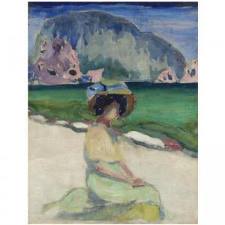

After a moment, he replaced his glasses, turned his head and looked to his right. There, he thought he saw someone approaching along the surf’s edge. As the image neared his vantage point, it appeared to be a woman in a loose-fitting white summer dress, her bare legs and feet kicking through foam, drifting seaweed and sand. They were alone — she did not appear to notice him. She paused, stooped to pick up a piece of driftwood and cast it off into the darkening waves. The artist stared at her; she seemed familiar.

The young woman turned and looked up at the dune. Raising her hand to shade her eyes against the setting sun, she spotted the artist. She smiled, waved and then ran toward the narrow trail that led from the beach to the summit. The woman soon reached the spot where the artist stood transfixed and expectant. But what was it he anticipated? He searched his memory the way you rummage through an old box stored in the back of a dark closet. Try as he might, he could not find what he was looking for. He only stared in wonder at her youth, her vitality — her simple, natural beauty.

“Oh Bob, I knew I’d find you here.” She said his name, and he knew the voice. But there was something vague and remote about the sound, like a recording playing at a distance. As she waited for his reply, the young woman reached down, shook the sand from her skirt and dusted her legs. Then she looked up at him and stared. “Well, cat got your tongue?”

“I’m sorry, Ellen, I didn’t expect you.” Someone replied, but it wasn’t the old artist, though he recognized the voice. Then he saw a young man walk over to the girl and take her hand. As the scene played out, the artist stood fixed to the spot like a shackled prisoner, as though he were being forced to watch and listen. The young man had news; he was going to Barcelona on a scholarship.

“Barcelona?” the girl questioned. “In Spain?”

The young man laughed, and the artist detected cruelty in the laughter. “Well yes, in Spain, unless they’ve gone and moved it.”

The young woman looked down at the sand. “That’s not funny.” No it wasn’t funny, the artist thought, although he wasn’t quite sure why it wasn’t funny. He tried to say something; he moved his lips, but the words were not his. They were the young man’s.

“It’s a great opportunity, Ellie. You wouldn’t want to hold me back, would you?”

The girl agreed — she didn’t want the young man to miss out on something so important. They talked for a while about their plans. He would be back in two years, or three at most. They would correspond frequently and regularly; she would save up for the fare and pay him a visit. That would be wonderful; he was sure she’d love Spain, and so forth.

All the while, the artist thought the young man insincere. The old man wanted to warn the girl — she shouldn’t wait, she shouldn’t trust, she shouldn’t grieve. The young man wasn’t worth it.

The couple stopped talking. They kissed, said good-bye and the girl walked away. The old artist sensed sadness in her expression, her gestures and the way she walked. She knew their relationship was over. The artist had learned how to read and draw emotions; that was his craft — and he had sacrificed much to acquire it. He could easily capture her mood in a sketch, a quick study. But he couldn’t see the young man’s face; only the back of his head. The artist decided to wipe the youth from his composition.

The old man turned and gazed after the woman. She walked down to the beach and up the shoreline until she rounded the headland and disappeared.

Night came; the dunes and sea glistened in moonlight, the wind stiffened. The artist shivered. He buttoned his jacket, closed his sketchpad and put away his pastels. Then, for an instant, he stared at the shadowy headland where the ghost-like figure had gone. “I knew her once,” he thought. “Does she belong in my picture?” But his memory failed him. His once keen perception had dulled like a worn old blade that resists the hone. “Too dark, too cold — too late,” he muttered.

The artist lifted himself slowly — aching muscles, sore joints, brittle bones. He turned his bent back on the beach and an obscure trail of footprints washing away in the tide. As he puffed up the steep incline, he wondered if he had enough strength left for the long walk home. LS

The dunes undulated, a serpent wriggling its way round the coastline. A mild breeze blew in from the ocean, rustling the green scrub and rattling the yellow, white and blue wildflowers that burst in bright patches over the dun, sandy heights. A few gulls soared overhead. Their cries, the repetitious washing of surf on the shore, and the wind soughing through the sparse foliage were the only sounds heard in this remote place.

The artist stopped sketching. He set down his pad, pulled off his wire-rimmed glasses and rubbed his tired eyes. A ray cast by the dying sun slanted across his white-stubbled jaw, highlighting his hard, thin face like a moonbeam limning a carving on a headstone.

After a moment, he replaced his glasses, turned his head and looked to his right. There, he thought he saw someone approaching along the surf’s edge. As the image neared his vantage point, it appeared to be a woman in a loose-fitting white summer dress, her bare legs and feet kicking through foam, drifting seaweed and sand. They were alone — she did not appear to notice him. She paused, stooped to pick up a piece of driftwood and cast it off into the darkening waves. The artist stared at her; she seemed familiar.

The young woman turned and looked up at the dune. Raising her hand to shade her eyes against the setting sun, she spotted the artist. She smiled, waved and then ran toward the narrow trail that led from the beach to the summit. The woman soon reached the spot where the artist stood transfixed and expectant. But what was it he anticipated? He searched his memory the way you rummage through an old box stored in the back of a dark closet. Try as he might, he could not find what he was looking for. He only stared in wonder at her youth, her vitality — her simple, natural beauty.

“Oh Bob, I knew I’d find you here.” She said his name, and he knew the voice. But there was something vague and remote about the sound, like a recording playing at a distance. As she waited for his reply, the young woman reached down, shook the sand from her skirt and dusted her legs. Then she looked up at him and stared. “Well, cat got your tongue?”

“I’m sorry, Ellen, I didn’t expect you.” Someone replied, but it wasn’t the old artist, though he recognized the voice. Then he saw a young man walk over to the girl and take her hand. As the scene played out, the artist stood fixed to the spot like a shackled prisoner, as though he were being forced to watch and listen. The young man had news; he was going to Barcelona on a scholarship.

“Barcelona?” the girl questioned. “In Spain?”

The young man laughed, and the artist detected cruelty in the laughter. “Well yes, in Spain, unless they’ve gone and moved it.”

The young woman looked down at the sand. “That’s not funny.” No it wasn’t funny, the artist thought, although he wasn’t quite sure why it wasn’t funny. He tried to say something; he moved his lips, but the words were not his. They were the young man’s.

“It’s a great opportunity, Ellie. You wouldn’t want to hold me back, would you?”

The girl agreed — she didn’t want the young man to miss out on something so important. They talked for a while about their plans. He would be back in two years, or three at most. They would correspond frequently and regularly; she would save up for the fare and pay him a visit. That would be wonderful; he was sure she’d love Spain, and so forth.

All the while, the artist thought the young man insincere. The old man wanted to warn the girl — she shouldn’t wait, she shouldn’t trust, she shouldn’t grieve. The young man wasn’t worth it.

The couple stopped talking. They kissed, said good-bye and the girl walked away. The old artist sensed sadness in her expression, her gestures and the way she walked. She knew their relationship was over. The artist had learned how to read and draw emotions; that was his craft — and he had sacrificed much to acquire it. He could easily capture her mood in a sketch, a quick study. But he couldn’t see the young man’s face; only the back of his head. The artist decided to wipe the youth from his composition.

The old man turned and gazed after the woman. She walked down to the beach and up the shoreline until she rounded the headland and disappeared.

Night came; the dunes and sea glistened in moonlight, the wind stiffened. The artist shivered. He buttoned his jacket, closed his sketchpad and put away his pastels. Then, for an instant, he stared at the shadowy headland where the ghost-like figure had gone. “I knew her once,” he thought. “Does she belong in my picture?” But his memory failed him. His once keen perception had dulled like a worn old blade that resists the hone. “Too dark, too cold — too late,” he muttered.

The artist lifted himself slowly — aching muscles, sore joints, brittle bones. He turned his bent back on the beach and an obscure trail of footprints washing away in the tide. As he puffed up the steep incline, he wondered if he had enough strength left for the long walk home. LS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed